Background

This past year, we published the first nationwide estimate of the incarcerated illegal immigrant population.3 That 2017 brief focused on incarceration rates for 2014. The public demand for that brief was so large that it prompted us to update the estimates using 2016 inmate data from the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey (ACS). In other sources, estimates of the total criminal immigrant population vary widely—from about 820,000 according to the Migration Policy Institute to 1.9 million according to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—but the number of incarcerated illegal immigrants is important and possible to estimate.4

Previous empirical studies of immigrant criminality generally find that immigrants do not increase local crime rates, are less likely to cause crime than their native-born peers, and are less likely to be incarcerated than native-born Americans.5 Illegal immigrant incarceration rates are not well studied; however, recent Cato Institute research based on data from the Texas Department of Public Safety found that, as a percentage of their respective populations, illegal immigrants represented 56 percent fewer criminal convictions than native-born Americans in Texas in 2015.6 The low illegal immigrant incarceration rate is consistent with other research that finds more targeting of immigrants does not reduce the crime rate, which would occur if they were more crime prone than natives.7

Methodology

This brief uses ACS data to estimate the incarceration rate and other demographic characteristics for immigrants ages 18 to 54 in 2016. Ordinarily collected by or under the supervision of correctional institution administrators, ACS inmate data are reliable; however, the quality of the data for the population that includes the incarcerated was not always so reliable. The response rate for the group quarters population, which includes those incarcerated in correctional facilities, was low in the 2000 Census.8 Recognizing that problem with data collection from the group quarters population, the Census Bureau substantially resolved it in the 2010 Census and the ACS, making several tweaks over the years that have continually improved the size and quality of the group quarters sample.9

The ACS counts the incarcerated population by their nativity and naturalization status, but local and state governments rarely record whether prisoners are illegal immigrants.10 As a result, we have to use common statistical methods to identify incarcerated illegal immigrant prisoners by excluding prisoners with characteristics that illegal immigrants are unlikely to have.11 In other words, we can identify likely illegal immigrants by looking at prisoners with individual characteristics highly correlated with being an illegal immigrant. Following guidance set by other researchers, those characteristics are that the immigrant must have entered the country after 1982 (the cut-off date for the 1986 Reagan amnesty), cannot have been in the military, cannot be receiving Social Security or Railroad Retirement Income, cannot have been covered by Veteran Affairs or Indian Health Services, is not a citizen of the United States, was not living in a household where somebody received food stamps (unless the individual had a child living with him or her who may be eligible if a U.S. citizen), and is not of Puerto Rican or Cuban origin if classified as Hispanic.

A major limitation of the ACS data is that our estimates of the illegal immigrant population will include some legal migrants who are here on other visas but whose answers are consistent with those of illegal immigrants. As a result, we likely overestimate the number of illegal immigrants who are incarcerated. Thus, because of ACS's data limitations, our estimates of the illegal immigrant incarcerated population and incarceration rate are likely greater than the actual population and rate.

Another limitation of the ACS data is that not all inmates in group quarters are in correctional facilities. Although most inmates in the public-use microdata version of the ACS are in correctional facilities, the data also include those in mental health and elderly care institutions and in institutions for people with disabilities.12 These inclusions add ambiguity to our findings about the illegal immigrant population but not about the immigrant population as a whole, because the ACS releases macrodemographic snapshots of inmates in correctional facilities, which allows us to check our work.13

The above-mentioned ambiguity in illegal immigrant incarceration rates prompted us to narrow the age range to those who are ages 18 to 54. This age range excludes most inmates in mental health and retirement facilities. Few prisoners are under age 18, many in mental health facilities are juveniles, and many of those over age 54 are in elderly care institutions. Additionally, few illegal immigrants are elderly, whereas those in elderly care institutions are typically over age 54.14 As a result, narrowing the age range does not exclude many individuals from our analysis. We are more confident that our methods do not cut out many prisoners because winnowing the age range reduces their numbers in the 18 to 54 age range to only 0.09 percent below that of the ACS snapshot.15 Natives in our results include both those born in the United States and those born abroad to American parents.

Controlling for the size of the population is essential for comparing relative incarceration rates between the native-born, illegal immigrant, and legal immigrant subpopulations. Thus, we report the incarceration rate as the number of incarcerations per 100,000 members of each particular subpopulation just as most government agencies do.16

Incarcerations

An estimated 1,955,951 native-born Americans, 117,994 illegal immigrants, and 43,618 legal immigrants were incarcerated in 2016. The incarceration rate for native-born Americans was 1,521 per 100,000, 800 per 100,000 for illegal immigrants, and 325 per 100,000 for legal immigrants in 2016 (Figure 1). Illegal immigrants are 47 percent less likely to be incarcerated than natives. Legal immigrants are 78 percent less likely to be incarcerated than natives. If native-born Americans were incarcerated at the same rate as illegal immigrants, about 930,000 fewer natives would be incarcerated. Conversely, if natives were incarcerated at the same rate as legal immigrants, about 1.5 million fewer natives would be in adult correctional facilities.

The ACS data include illegal immigrants incarcerated for immigration offenses and in ICE detention facilities.17 Removing the immigration offenders by subtracting the 13,000 convicted for immigration offenses and the 34,379 in ICE detention facilities on any given day lowers the illegal immigrant incarceration rate to 479 per 100,000.18

Robustness Checks for Counting the Illegal Immigrant Population

Because our chosen ACS variables could have affected the number of illegal immigrants we identified in the data, we altered some of the variables to see if the results significantly changed. First, we included illegal immigrants who lived in households with users of means-tested welfare benefits. Illegal immigrants do not have access to these benefits, but U.S. citizens and some lawful permanent residents in their households do. This adjustment dropped the illegal immigrant incarceration rate to 760 per 100,000, the legal immigrant incarceration rate remained at 325 per 100,000, and the adjustment did not affect the native incarceration rate.

Our second robustness check excluded all immigrants who entered the United States after 2008. Immigrants on lawful permanent residency can apply for citizenship after five years, guaranteeing that most of the lawful permanent residents who are able to naturalize have done so, which decreases the pool of potential illegal immigrants in our sample. This robustness check shrinks the size of the nonincarcerated illegal immigrant subpopulation relative to those incarcerated and, thus, slightly raises the rate of illegal immigrant incarceration to about 880 per 100,000. These variable changes did not alter our results enough to undermine our confidence in the findings.

Demographic and Social Characteristics

Incarceration rates vary widely by race and ethnicity in the United States, even within each immigrant category (Table 1). By race and ethnicity, every group of legal and illegal immigrants has a lower incarceration rate than natives of the same race or ethnicity. The incarceration rate for illegal immigrants of all races and ethnicities is lower than the incarceration rate for native-born white Americans. The racial and ethnic incarceration rates reported here are close to those in the ACS's macrodemographic snapshot of adult correctional facilities.19

Immigrants from certain parts of the world are more likely to be incarcerated than others (Table 2). Of all legal immigrants, those from Latin America, Other Asia, and Africa have the three highest incarceration rates. For illegal immigrants, those from Latin America have the highest incarceration rate of any group—in part because they are more likely to be incarcerated for immigration offenses and in ICE detention facilities than immigrants from any other region—followed by those from Africa. Across all broad groups, those individuals born in Other countries have the highest incarceration rate followed by those born in the United States. The distribution of prisoners by their immigration status and region of origin shows that 6.48 percent of all prisoners are from Latin America whereas 91.69 percent were born in the United States (Table 3).

Almost 89 percent of all prisoners are men, whereas only 11.17 percent are women (Table 4). Legal and illegal immigrant women are less likely to be incarcerated than native-born women.

Prisoners in every group are less educated (Table 5). The percentage of all adult natives who have some college education or above is 62.8 percent, whereas 18.5 percent of native-born prisoners have the same level of education. A total of 20.9 percent of legal immigrant prisoners and 12.6 percent of illegal immigrant prisoners have some college education or above, percentages that are lower than the percentages of their respective subpopulations with the same level of education.20 Those in every immigration category who are highly educated tend to avoid incarceration.

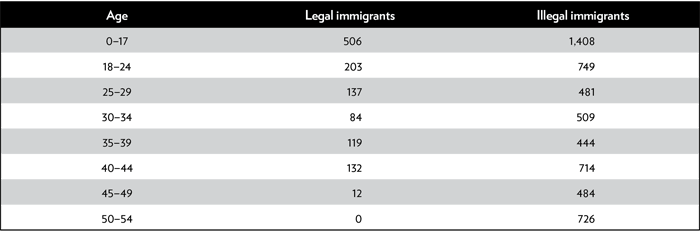

Native-born Americans and illegal immigrants have higher incarceration rates when they are young (Table 6). The peak incarceration rate for natives is between ages 30 and 34, and it is between ages 18 and 24 for illegal immigrants. The legal immigrant incarceration rate varies much less over time, peaking between ages 25 and 29, declining until age 34, and then increasing again to its youthful heights from age 35 to 49 before falling again. The incarceration rates for legal and illegal immigrants generally increase with the amount of time that they have spent in the United States (Table 7).

Related to the amount of time immigrants have spent in the United States, illegal and legal immigrants who immigrate at a younger age are more likely to be incarcerated (Table 8). Illegal immigrants who arrive between ages 0 and 17 are 220 percent more likely to be incarcerated than those who arrive at later ages, suggesting that illegal immigrants old enough to choose to break American immigration laws are more law-abiding than those who were brought here as minors.

Table 8

Incarceration rates for immigrants by their age of arrival in the United States, ages 18–54

Source: Authors' analysis of the 2016 American Community Survey data.

Note: Rates are per 100,000 residents in each subpopulation.

The pattern is even more pronounced for legal immigrants: those who immigrated between the ages of 0 and 17 were 224 percent more likely to be incarcerated than legal immigrants who came at later ages, again suggesting that those old enough to choose to come legally to the United States are more law-abiding. At least two nonmutually exclusive theories can explain why those who entered in their youth have higher incarceration rates. First, spending part of one's childhood in the relatively high-crime United States assimilates many immigrants to our high-crime culture. A second theory is that those who decide to come here have some systematically different characteristics that make them less likely to be incarcerated, whereas those who are too young to make the decision to immigrate do not.

Conclusion

Legal and illegal immigrants were even less likely to be incarcerated than native-born Americans in 2016 than they were in 2014.21 Those incarcerated do not represent the total number of immigrants who can be deported under current law or the complete number of convicted immigrant criminals who are in the United States, but merely those who are incarcerated. The younger the immigrants are upon arrival in the United States and the longer they are here, the more likely they are to be incarcerated as adults. This brief provides numbers and demographic characteristics to better inform the public policy debate over immigration and crime.

Notes

1. "Executive Order: Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States," Executive Order of the President, January 25, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-enhancing-public-safety-interior-united-states/.

2. Lesley Stahl, "President-Elect Trump Speaks to a Divided Country on 60 Minutes," CBS News, November 13, 2016, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/60-minutes-donald-trump-family-melania-ivanka-lesley-stahl/.

3. Michelangelo Landgrave and Alex Nowrasteh, "Criminal Immigrants: Their Numbers, Demographics, and Countries of Origin," Cato Institute, Immigration Research and Policy Brief no. 1, March 15, 2017.

4. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Salaries and Expenses," Congressional Submission (Washington: Department of Homeland Security, 2013), p. 61, https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/mgmt/dhs-congressional-budget-justification-fy2013.pdf; Marc R. Rosenblum, "Understanding the Potential Impact of Executive Action on Immigration Enforcement," Migration Policy Institute, July 2015, p. 11, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/understanding-potential-impact-executive-action-immigration-enforcement.

5. Graham C. Ousey and Charis E. Kubrin, "Immigration and Crime: Assessing a Contentious Issue," Annual Review of Criminology 1, no. 1 (2018); Kristin F. Butcher and Anne Morrison Piehl, "The Role of Deportation in the Incarceration of Immigrants," in Issues in the Economics of Immigration, ed. George J. Borjas (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000), pp. 351–86; Kristin F. Butcher and Anne Morrison Piehl, "Why Are Immigrants' Incarceration Rates So Low? Evidence on Selective Immigration, Deterrence, and Deportation," NBER Working Paper no. 13229, National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2007; Alex Nowrasteh, "Immigration and Crime—What the Research Says," Cato at Liberty, July 14, 2015, https://www.cato.org/blog/immigration-crime-what-research-says.

6. Alex Nowrasteh, "Criminal Immigrants in Texas: Illegal Immigrant Conviction and Arrest Rates for Homicide, Sexual Assault, Larceny, and Other Crimes," Cato Institute, Immigration Research and Policy Brief no. 4, February 26, 2018.

7. Thomas J. Miles and Adam B. Cox, "Does Immigration Enforcement Reduce Crime? Evidence from Secure Communities," Journal of Law and Economics 57, no. 4 (2014): 937–73; Elina Treyger, Aaron Chalfin, and Charles Loeffler, "Immigration Enforcement, Policing, and Crime," Criminology & Public Policy 13, no. 2 (2014): 285–322; Andrew Forrester and Alex Nowrasteh, "Do Immigration Enforcement Programs Reduce Crime? Evidence from the 287(g) Program in North Carolina," Cato Institute, Cato Working Paper no. 52, April 11, 2018.

8. Constance F. Citro, Danile L. Cork, and Janet L. Norwood, eds., The 2000 Census: Counting under Adversity (Washington: The National Academies Press, 2004), pp. 297, 488.

9. Constance F. Citro and Graham Kalton, eds., Using the American Community Survey: Benefits and Challenges (Washington: The National Academies Press, 2007), pp. 170–73.

10. Steven Ruggles et al., "Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0" (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2015); Figure 1: Incarceration rates and characteristics of immigrants incarcerated in the United States who are between ages 18 and 54 for the years 2008 to 2014.

11. Enrico A. Marcelli and David M. Heer, "The Unauthorized Mexican Immigrant Population and Welfare in Los Angeles County: A Comparative Statistical Analysis," Sociological Perspectives 41, no. 2 (1998): 279–302; Robert Warren, "Democratizing Data about Unauthorized Residents in the United States: Estimates and Public-Use Data, 2010 to 2013," Journal on Migration and Human Security 2, no. 4 (2014): 305–28; Pia M. Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny, "Do State Work Eligibility Verification Laws Reduce Unauthorized Immigration?" IZA Journal of Migration 5, no. 1 (2016): 1–17.

12. Butcher and Piehl, "The Role of Deportation in the Incarceration of Immigrants"; Butcher and Piehl, "Why Are Immigrants' Incarceration Rates So Low?"

13. U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table S2601B, "Characteristics of the Group Quarters Population by Group Quarters Type."

14. Jeffrey S. Passel and D'Vera Cohn, "A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States," Pew Research Center, April 14, 2009, http://www.pewhispanic.org/2009/04/14/a-portrait-of-unauthorized-immigrants-in-the-united-states/.

15. American Community Survey, "Characteristics of the Group Quarters Population by Group Quarters Type."

16. Bureau of Justice Statistics, "Crime and Justice in the United States and in England and Wales, 1981–1996," https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/html/cjusew96/cpp.cfm.

17. U.S. Census Bueau, "2016 American Community Survey/Puerto Rico Community Survey Group Quarters Definitions," https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/code-lists.2016.html.

18. E. Ann Carson, "Prisoners in 2016," U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ251149, January 2018, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p16.pdf; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Department of Homeland Security, Congressional Justification, Fiscal Year 2018, p. 14, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/CFO/17_0524_U.S._Immigration_and_Customs_Enforcement.pdf.

19. American Community Survey, "Characteristics of the Group Quarters Population by Group Quarters Type."

20. Passel and Cohn, "A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States."

21. Landgrave and Nowrasteh, "Criminal Immigrants: Their Numbers, Demographics, and Countries of Origin."